It is often believed that spending more time on social media makes a citizen more skeptical of the EU. Martin Moland and Asimina Michailidou argue that this assumption is too simplistic.

A fresh look at a common assumption

One of the most hotly debated issues of the last years has been how social media has changed politics and public debate. Whether it is the effect of so-called Russian “bots” sharing misinformation related to the 2016 presidential election in the US, or misleading information regarding Brexit leading up to the vote in the same year, the consensus that seems to have emerged is of social media as a negative and polarizing force.

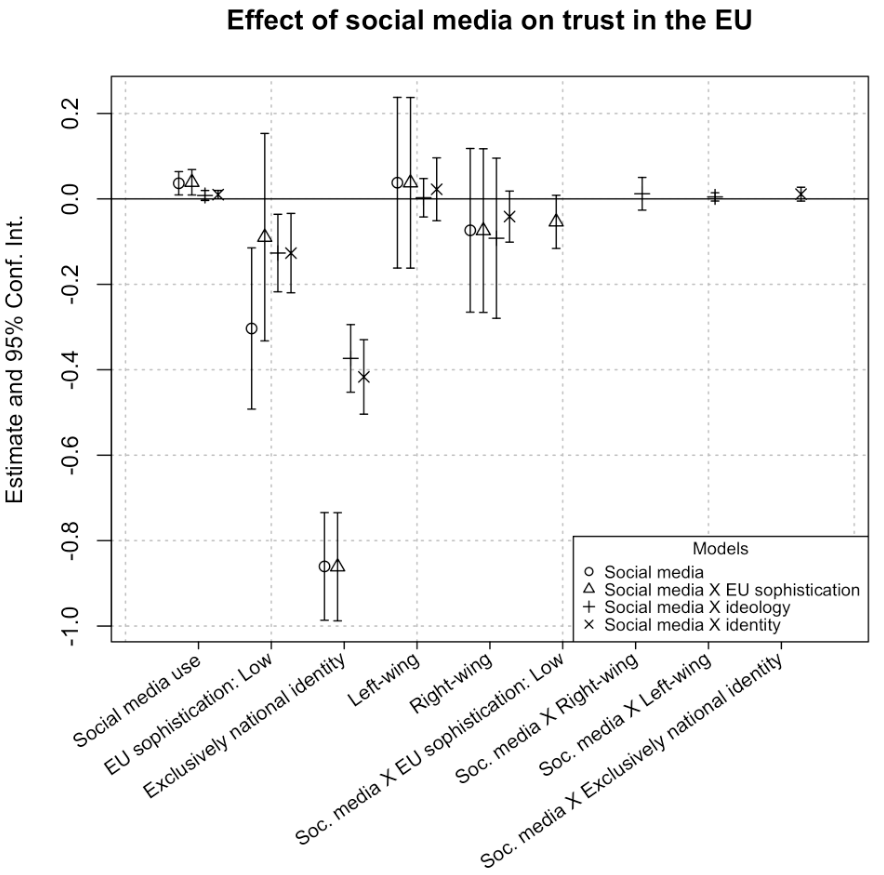

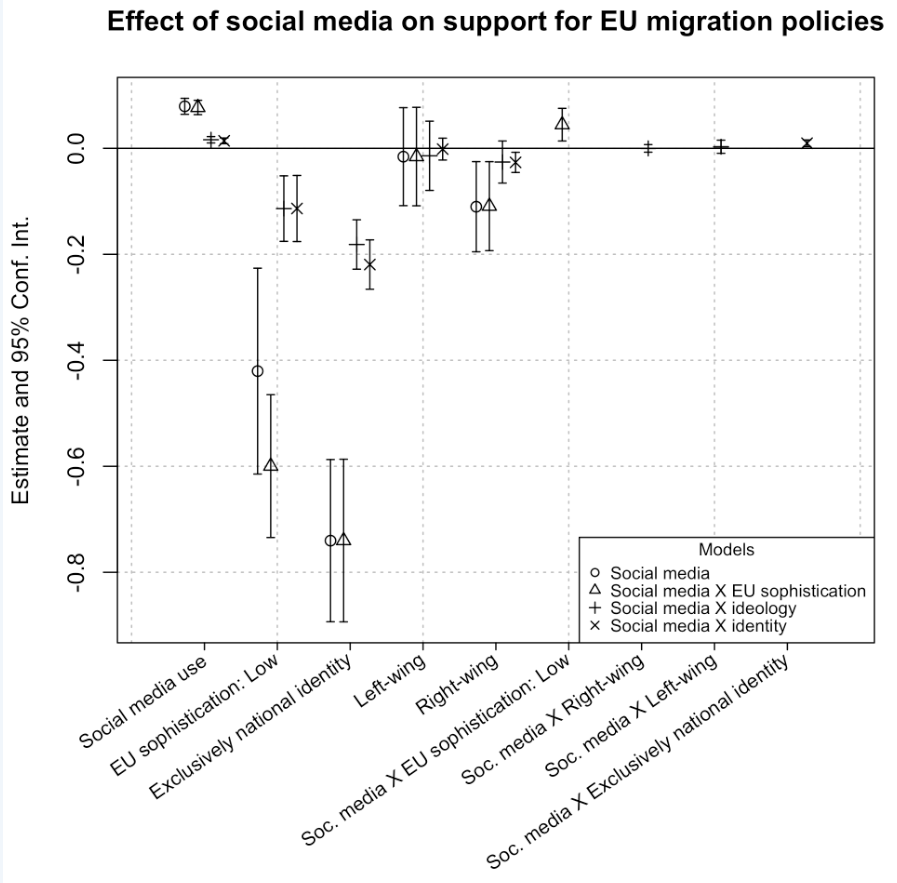

In our new paper, “News, misinformation and social media: exploring the effect of social media as polarising force or neutral mediators”, we ask whether exposure to social media leads to a decreased trust in the European Union, whether on its own or in combination with other factors that may themselves lead to decreased support for European integration. Previous research has found both that exposure to Eurosceptic social media content decreases support for the EU (Hameleers, 2019) and that such Eurosceptic messages are prevalent features of online news information about the EU (Michailidou, 2015). However, the literature finding such a correlation primarily uses experimental methods while relying on a small number of respondents. To test whether a similar correlation exists at the societal level, we repurposed Eurobarometer data from 2016 and 2018 from 27 EU member states, controlling for a wide range of individual-level factors that potentially confounds the relationship between social media use and support for the EU.

Fig 2. (right): Support for common migration policies. All effects log-odds. Cluster-robust 95% CI. Fixed effects for country and year omitted.

Click on images to enlarge.

We expected that this negative framing of European integration in online media would decrease trust in the EU among heavy users of social media and lead to decreased support for common migration policies. We also anticipated that those who were already “predisposed” to be skeptical of EU integration would have their views reinforced by heavier exposure to social media. This is because previous research has found that online debate reinforces previously held opinions, even if social media users are unlikely to avoid confronting content with which they disagree (Karlsen et al., 2017).

Social media habits don’t make opinion – but perhaps the agora does

What we found was in fact the opposite: There is little to suggest that social media use decreases support for European integration, either on its own or when interacted with indicators of Euroscepticism. This applies both to a general trust in the EU as an institution and to specific support for common migration policies at the EU level.

One objection to the need for increased transparency at the EU level is that details might be taken out of context and used to polarize opinions about the EU. However, our results suggest that the societal effect of exposure to polarized social media on support for the EU is minimal.

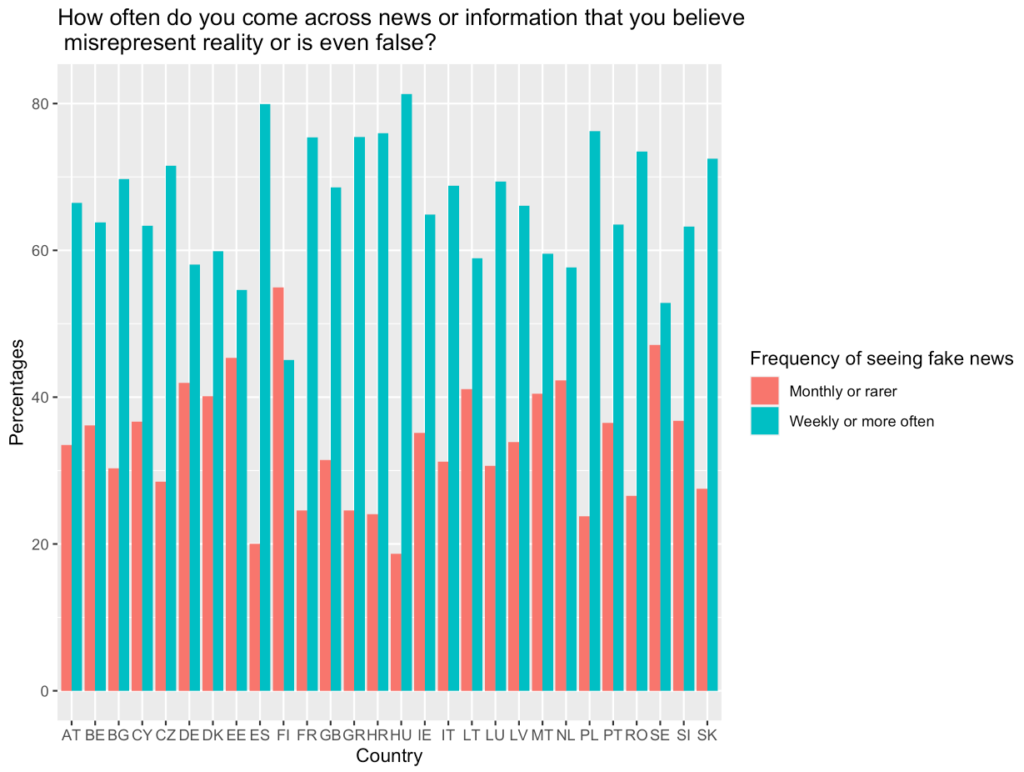

Our findings remained the same even in the cases of Finland and Hungary, the two countries where the levels of weekly self-reported exposure to perceived “fake news” are lowest and highest in the EU respectively. We found hardly any correlation between social media use and decreased support for European integration also when we interacted social media use with levels of self-reported exposure to “fake news”. The fact that very few of the coefficients related to social media use are statistically significant in our study suggests that there is no clear-cut relationship between social media use and support for European integration. While there is of course an uncertainty inherent to such self-reporting, our results suggest that any conclusion regarding the societal effect of social media use must be wary of aggregating individual-level conclusions to the societal level.

This shows how structural features of media systems and public spheres potentially mitigate individual social media effects. What these structural features are lies outside the scope of our paper. However, our results suggest that there is much work to be done in explaining exactly how social media use that appears to decrease trust in institutions when measured in an experimental setting loses its ability to do the same when the same respondent uses social media as part of a bigger media mix. This is also closely connected to discussions about the feasibility and value of transparency.

Click on image to enlarge.

One objection to the need for increased transparency at the EU level is that individual details might be taken out of context and used as the basis for a discourse that further polarizes opinions about the EU. This danger might assumedly be larger in social media, where such details might become amplified and serve as the basis of a polarized discourse. However, our results suggest that the societal effect of such exposure on support for the EU is minimal. There may of course be other challenges related to transparency inside the EU, but there is little to suggest that social media exposure to more or less controversial details of EU policy will in itself be enough to drive distrust in the EU.

A link to the article will be made available here soon.

Martin Moland is a doctoral candidate at the ARENA Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo. Asimina Michailidou is a senior researcher at the ARENA Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo.

One reply on “Is there a relationship between Facebook, fake news and support for the EU? It’s complicated.”

[…] blog post was originally published on The Open Government in the EU Blog and has been republished here with […]